timeless PinkLetters, translated from our Spanish Substack for English-speaking readers.

Skimming the Market (Pricing, Part I)

What microeconomics teaches us about startup pricing and how Good–Better–Best can turn customer benefit into real growth.

Pricing is a vast topic, so I decided to split it into two chapters. Part I grounds the microeconomics of pricing in a practical case: willingness to pay, demand curves, and price discrimination. Part II will focus on operations: how to avoid feature creep, define a healthy plan mix, learn from the “Best” so that value cascades down, and use promotions to retain customers without damaging your positioning.

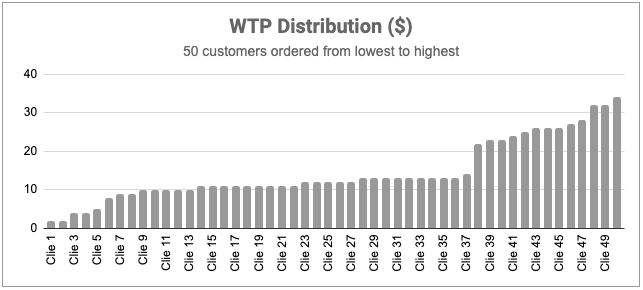

Distribution of Willingness to Pay (WTP)

Imagine a universe of 50 potential customers for an inventory management SaaS. Each one has a different WTP (willingness to pay): some would only pay a little, others much more, depending on their complexity, margins, or budget.

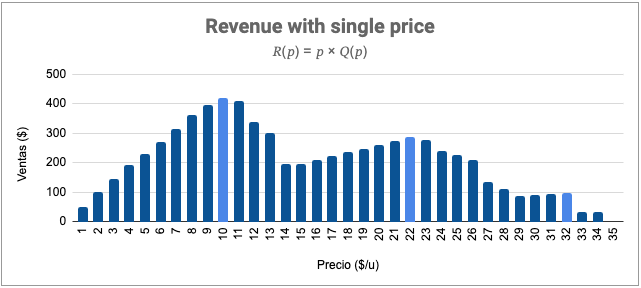

Single Price and Consumer Surplus

Suppose we set the price at $10. The first 8 customers drop out (their WTP is below $10). The remaining 42 pay $10, even though many would have paid more. That gap is what microeconomics calls consumer surplus: extra benefit customers capture when they pay less than their maximum willingness to pay.

Our revenue is $10 × 42 = $420, while consumer surplus is $268.

What happens if we raise the price to $22? The market shrinks: only 13 customers buy, with total revenue of $286 and much lower surplus. These customers are barely convinced, which means a higher risk of churn.

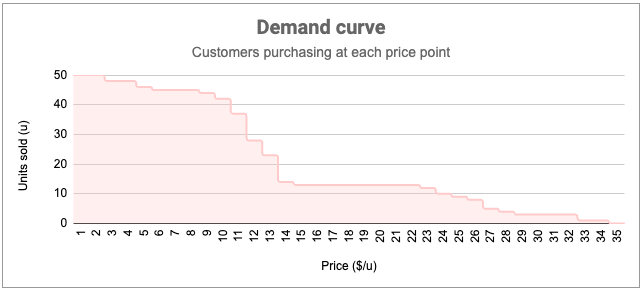

Demand Curve and Total Revenue

To find the best single price, we construct the demand curve: how many customers would buy at each price point.Multiplying price by units sold gives the total revenue curve:

- The global maximum is at $10.

- Local maxima appear at $22 and $32.

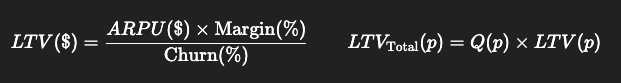

From Revenue to Value: LTV and Total LTV

The problem with focusing only on revenue is that it gives you a snapshot of one month. In SaaS, what matters is not how much you collect today, but how much value each cohort retains over time.

Raising prices may increase ARPU, but it also reduces Q(p) (fewer customers with WTP ≥ p) and often increases churn. The goal is not the highest ARPU, but the maximum Total LTV.

In the example below, we assume a low marginal cost, margins improving slightly with higher prices, and churn increasing as the product feels more expensive:

Although $24 gives a higher unit LTV, the smaller customer base drags down Total LTV. At $15, lower ARPU is offset by higher volume and better retention, delivering the highest overall value.

The lesson: the right price is not the one that maximizes today’s revenue, but the one that sustains the most value over time.

Price Discrimination: Good–Better–Best

Microeconomics offers a solution: price discrimination. In startups, this usually takes the form of Good–Better–Best plans with clear fences: number of users, SKUs, reports, SLA, security, or integrations. This way, customers self-select into the plan that matches their needs.

Suppose we launch three plans:

- Good = $10 (42 customers → $420)

- Better = $22 (13 customers pay $12 extra → $156)

- Best = $32 (3 customers pay $10 extra → $30)

Total revenue = $606, a 44% improvement over the single-price case.

In this example we assumed perfect price discrimination: all customers with sufficient WTP move up to the higher plan. In practice, efficiency is never 100%. Some customers will remain in lower plans even if they could afford more. That’s why fences must be carefully designed so that upgrading feels natural and valuable.

This is what I call “skimming the market”: each higher plan adds an extra revenue layer, capturing more value from customers with higher WTP, without losing the mid-market.

Reflection and Closing

Price is not just a number: it is signal and selection. Signal, because it communicates category (too low and you sound like a toy; too high and you set expectations you can’t deliver). Selection, because it defines who you learn from: those who pay more often face the sharpest problems, and their demands reveal insights that can later be packaged down for the rest of the market.

The next time you think about pricing, don’t just ask how much you can charge—ask how much value you want to sustain. That’s the real game of optimizing Total LTV.

In Part II we’ll move to operations: avoiding feature creep, setting healthy plan mixes, learning from “Best” and cascading value down, and using promotions to retain without destroying positioning.